Toshiko Takaezu

American, 1922–2011

About Toshiko Takaezu

Born in Hawaii in 1922 to Japanese parents, Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011) began as a production potter. She studied ceramics in Hawaii with Claude Horan before training at the prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. There, she worked with master ceramist Maija Grotell (and became Grotell’s assistant) and later taught. The majority of Takaezu’s teaching career was spent in the art department at Princeton University, where she retired in 1992.

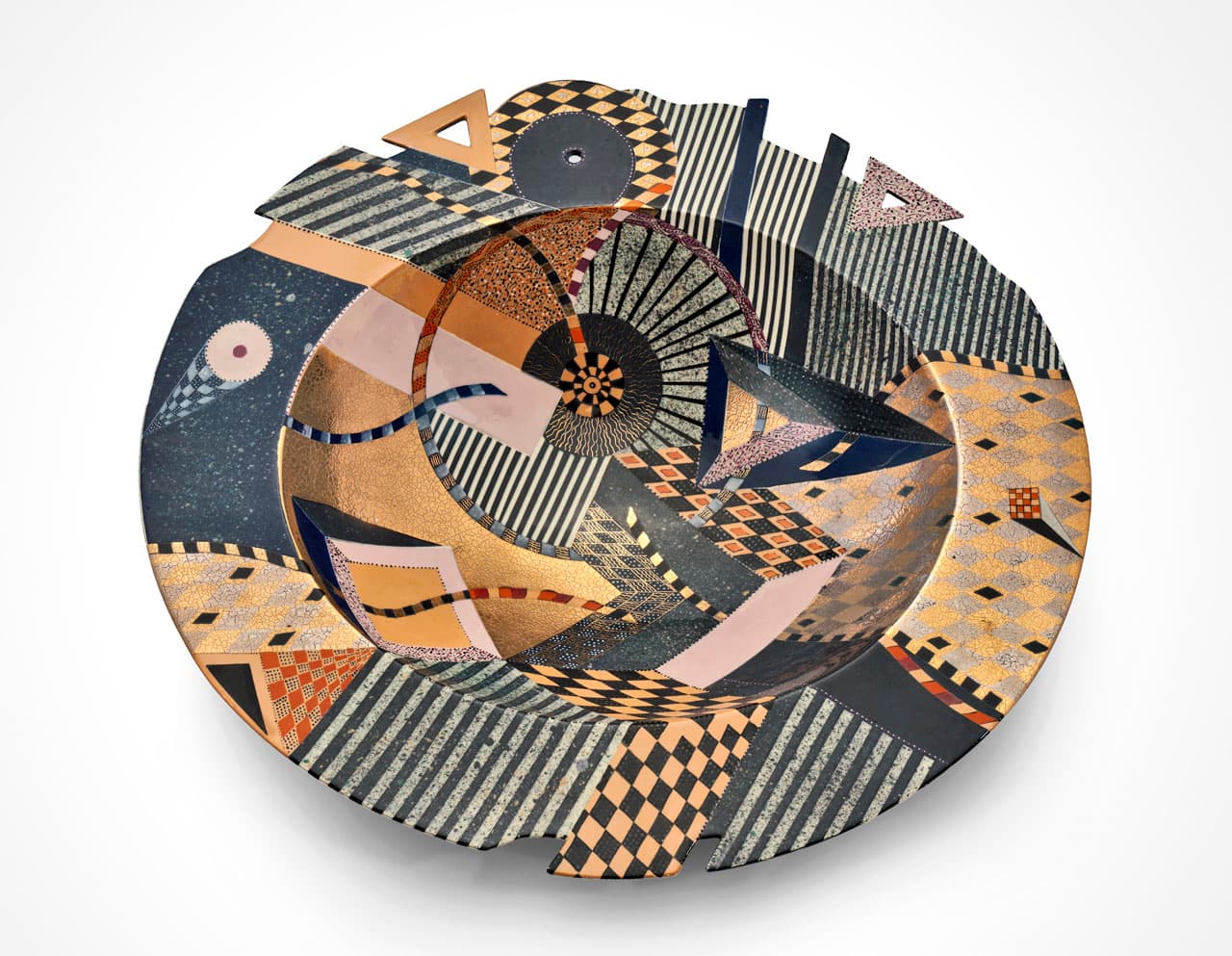

Today, Takaezu is a major figure among post-war era artists who pushed the clay medium beyond the utilitarian. Like many ceramists who rejected the assumption that a usable vessel must be the outcome of their creativity, Takaezu symbolically closed the mouth of her “pots.” Takaezu and others thus paralleled contemporary developments in painting and sculpture, which became divorced from representation. Takaezu in particular used this rejection of utility to control the aesthetic experience by creating sculptural forms unmediated by function. “You can’t put anything in, and you can’t take anything out,” she often stated.

Takaezu’s small, closed forms were made on the wheel, while larger pieces were built from coils over a period of hours or days. These forms were paddled or shaped by hand, resulting in softly modulated, rounded shapes. Takaezu then treated these forms as “three-dimensional canvases,” on which she achieved her greatest self-expression through a brush and glaze. Her signature “closed forms” boast finishes that include vibrant matte glazes on porcelain to the more subdued effects of ash and flame on stoneware in the Japanese anagama (cave-kiln) tradition. For her, this mode of painterly expression offered the perfect balance between traditional painting and sculptural presence. Although abstract, nearly all of Toshiko Takaezu’s forms were inspired by nature or geology, and sometimes by the human form.

Takaezu and her sister lived for a time in a Buddhist temple in Japan, where Takaezu studied Zen philosophy and the tea ceremony. This experience, coupled with her Buddhist upbringing, crystallized her belief that art and life were inseparable and that art-making stemmed from self-realization. Her organic, gourd-like forms resemble the vegetables she grew in her garden. “It's all connected with the garden, and the vegetables, and the process of growing,” she explained, “They’re all the same to me–one is not more important than the other...”

Other important elements in Takaezu’s work are kept secret. Few know that she often inscribed two or three words on the interior walls of her vessels–words that only a catastrophe can reveal. Another more obvious element–at least to those who have handled her pots–is that of sound. Each closed form contains one or more small pebbles of clay that reverberate inside. These emit a range of tones, from tiny pings to murmuring bass notes. Takaezu referred to this sound as another way of “sending messages.” This love of sound is metaphorical–echoing the earth–as do the pots themselves.