Black Artists in America Spotlight: Unity Lewis on artistic friendships and enduring legacy

November 26, 2025

Inspired by the exhibition Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial through September 11, Unity Lewis—a Sacramento-based artist, musician, and curator—sits down with Curator Francesca Wilmott to talk about his grandmother’s artwork and legacy.

In this interview, inspired by the exhibition Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial through September 11, Unity Lewis—a Sacramento-based artist, musician, and curator—sits down with Crocker Curator Francesca Wilmott to talk about his grandmother’s artwork, artistic friendships, and enduring legacy. Lewis and Wilmott unpack a lithograph titled Cleo (1996) by Lewis’s grandmother, Samella Lewis. Lewis and Wilmott are co-curating the 2028 Crocker exhibition, Black Artists in California: Nineteenth Century to Now.

Black Artists in America is on view at the Crocker Art Museum through January 11, 2026.

Interview:

FW: Black Artists in America is curated by Dr. Earnestine Lovelle Jenkins and organized by the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis. Dr. Jenkins brought together more than fifty artworks made by leading African American artists from 1976 to 2001. Within the exhibition, Samella Lewis belongs to an older generation, completing Cleo (1996) at age 73. How do you interpret your grandmother’s relationship to the young woman in Cleo?

UL: In Cleo, it appears to me that the subject is, at least in part, a self-portrait. Although I never heard anyone refer to my grandmother as Cleo, my research on this work revealed that “Cleo” was one of her nicknames. This connection feels fitting, as Cleo—or Clio—is also the name of the Greek muse of history, the daughter of memory. It is a perfect moniker for my grandmother, who is often regarded as the godmother of the Black Arts Movement for her work as a historian devoted to preserving our cultural legacy so that we might never forget.

I believe the yellow glow surrounding her face symbolizes her as an enlightened being. Yellow flowers traditionally represent joy, inner strength, and new beginnings—qualities my grandmother deeply associated with knowledge of self, culture, and history. Her lifelong pursuit of knowledge invigorated her spirit, which is perhaps why Cleo presents us with an image that is both wise and youthful. The cross in the background may signify the sacrifices my grandmother—and those who came before her—made to preserve our history and culture for future generations.

FW: What can you tell us about this later period in Samella Lewis’s career?

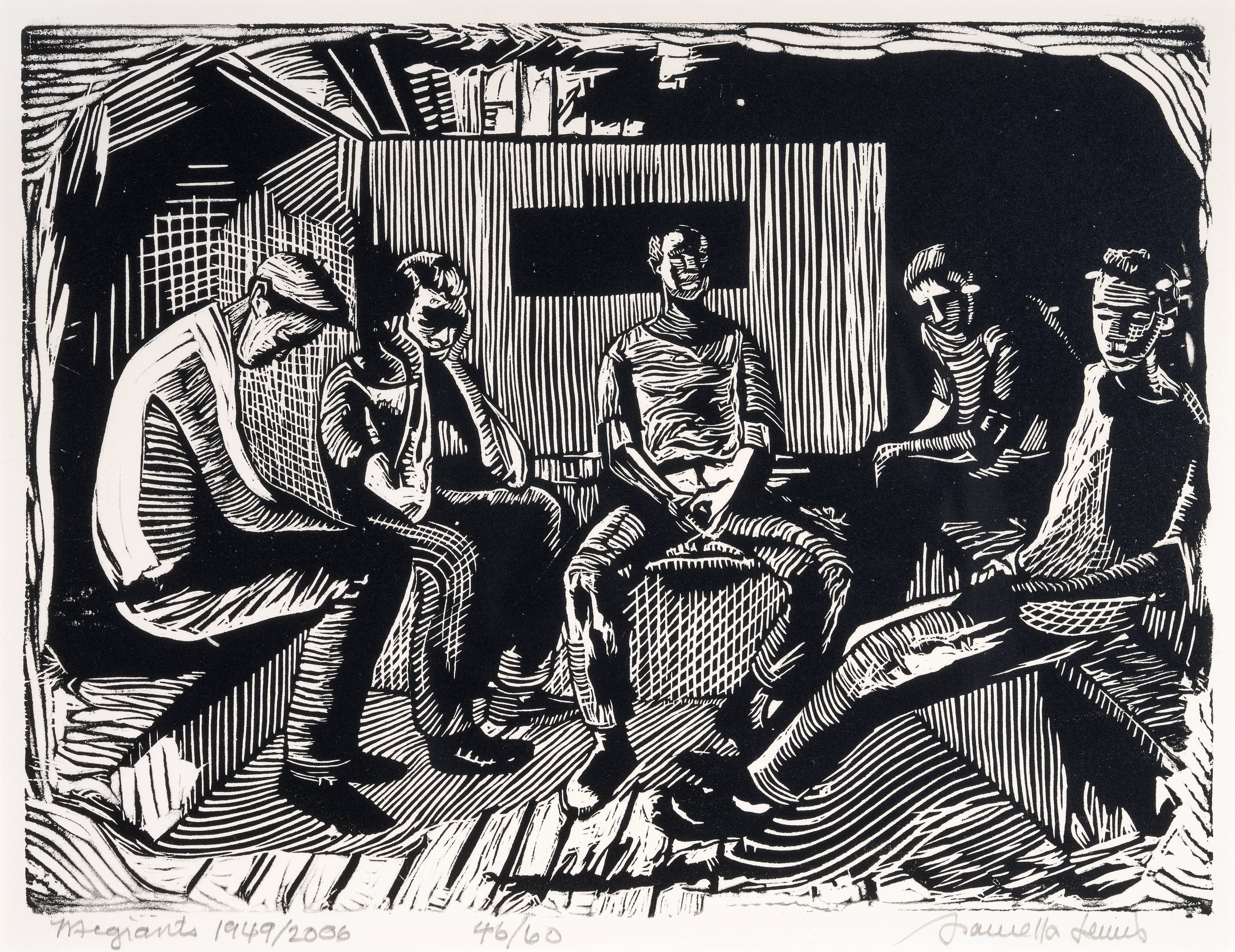

UL: Towards the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, my grandmother produced some of her most important linocuts while simultaneously expanding her range of techniques in printmaking and other mediums. Foundationally, however, I believe that drawing and painting were at the core of her practice.

From the 1970s through the 1980s, my grandmother created numerous drawings and paintings that reveal her growing mastery of using art as a language to convey her experiences and ideas. She primarily viewed art as an instrument of communication. As her body of work grew, she developed her own visual lexicon—stories, messages, and events that offered a window into a world seen through the eyes of an educated Black woman on a mission to both preserve and advance her culture through the arts.

From the 1980s into the 2000s, she produced many of her quintessential serigraphs and lithographs, including Cleo (1996), House of Shango (1992), Bayou Woman (2006), and Mother and Child (2007). She also issued second editions of earlier linocuts from the 1940s through the early 1970s during this time.

Samella Lewis did not limit herself to two-dimensional work during these years. In collaboration with the master sculptor Richmond Barthé, she re-cast many of the works included in his 1986 editions. It is also known that she experimented with sculpture herself, though such works are rare.

FW: Your grandmother's work transcends the canvas: she was a professor, a museum founder, printmaker, and a published author and book editor. Mentoring a younger generation of artists was a cornerstone of her practice. What was Samella Lewis’s approach to mentoring and how does that show up in her artwork?

UL: Regarding my grandmother’s approach to mentorship, there are three ways I can speak to it. Firstly, from personal experience, she was very hands-on with me in developing my formal training and deepening my understanding of technique—how to see overall shape, form, and composition. During the time I spent under her tutelage, she taught me countless lessons that refined my skills: how to truly see what was before me and recreate it without allowing preconceived ideas to cloud my vision, and how to draw form out of abstraction. When it came to subject matter, she imposed no limitations; instead, she emphasized the importance of perspective—cultivating one’s own artistic vocabulary as a means to move people emotionally and communicate powerful messages. She instilled in me a profound understanding of how art can serve as a tool not only for self-discovery but also for advancing humanity—challenging us to think critically and address the issues necessary for progress. She also taught me practical fundamentals such as how to organize, catalog, and price works of art.

Secondly, from what I observed of her relationships with others, she approached mentorship in a way that was uniquely tailored to each individual. Every person, she believed, has a distinct learning style and a personal history that shapes their artistic journey. Through mentorship and friendship alike, my grandmother helped people refine and polish their natural gifts into their own authentic voices of expression. She was always honest and direct—never offering false praise—because she understood that flattery could hinder growth. I personally received critiques that were difficult to hear at the time, but those moments proved to be some of the most transformative in my development as an artist.

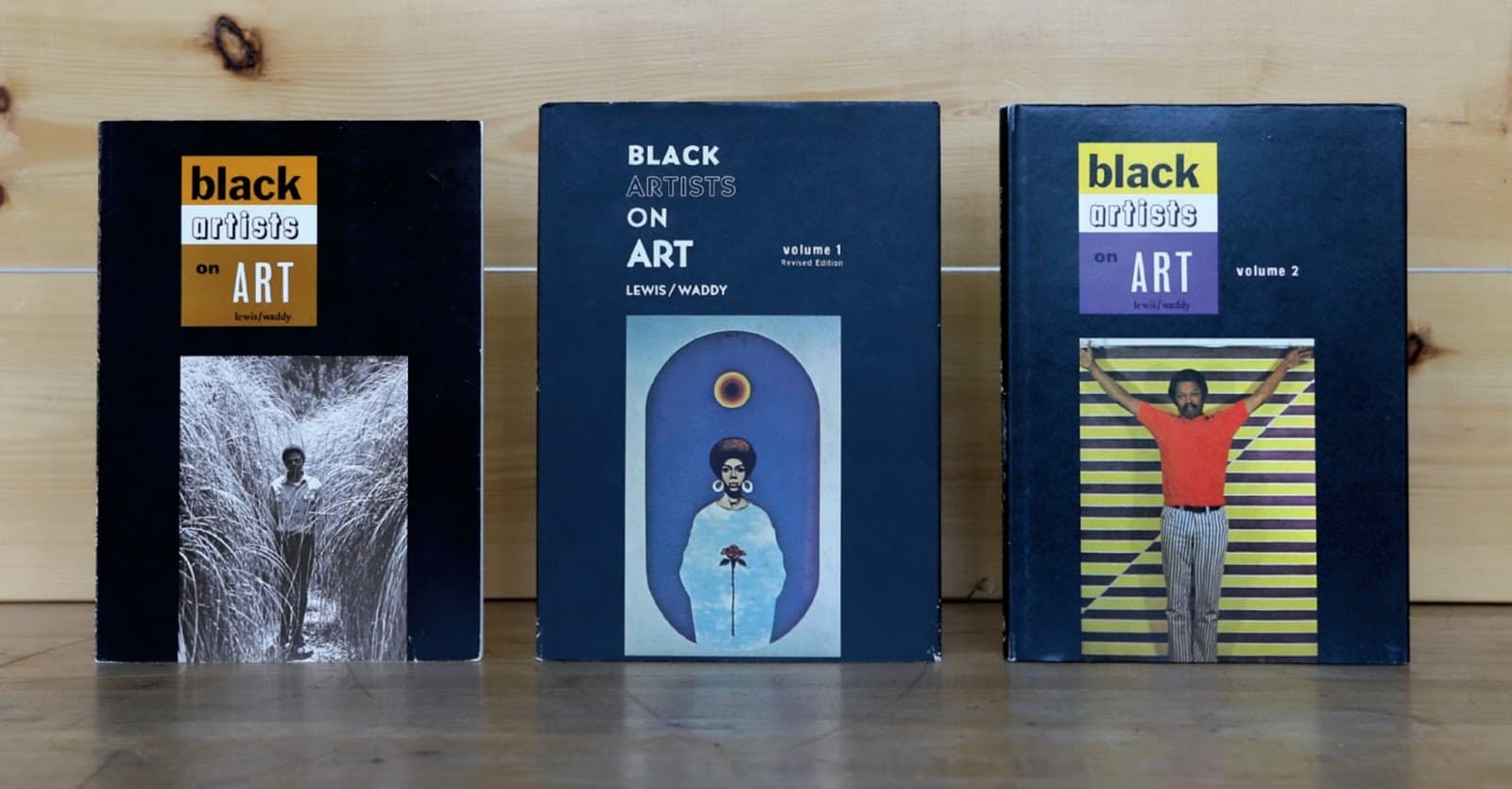

Lastly, her mentorship extended far beyond her immediate circle. Through her art, writing, and public work, she reached countless others who may never have met her in person. To me, the word educator is synonymous with Samella. She was always teaching, always offering gems of wisdom. I’ve met people who found her work to be a guiding light along their path. One friend, a historian of African American art, once told me that during college he struggled to find voices that reflected his own experience, as the curriculum focused heavily on Eurocentric perspectives. One day, buried in his college library, he discovered a book that changed his life, Black Artists on Art, co-compiled in 1969 by my grandmother and Ruth Waddy. He described it as his personal bible, the source of inspiration that motivated him to persist and ultimately become the scholar he is today. That is the kind of impact my grandmother had on the world, the legacy she left through her art, her words, and her unwavering dedication to uplifting others.

FW: Many of your grandmother’s friends also have work in Black Artists in America. Can you tell us about her relationships with some of the other artists in the show?

UL: I love that my grandmother’s work Cleo is displayed near a sculpture by Elizabeth Catlett and a piece by Jacob Lawrence. Both were not only mentors to her but also dear friends. They are two of the legendary Black artists who contributed to the Black Artists on Art book series, lending it the recognition and prestige that helped define its place in history.

Betye Saar—another pioneering Black artist and close family friend—essentially made her debut in Black Artists on Art. Her daughter, Alison Saar, was both a friend and student of my grandmother’s, continuing a beautiful intergenerational exchange of creativity and mentorship. The series also included one of the earliest published presentations of the works and words of David Hammons, who would go on to become one of the most influential contemporary artists of his generation. Romare Bearden and John Biggers were among her other close colleagues and creative peers.

For me, this exhibition feels like a family gathering—a reunion of kindred spirits whose lives and legacies were deeply intertwined through mentorship, friendship, and mutual inspiration. Seeing my grandmother’s work presented alongside so many artists who both influenced and were influenced by her is profoundly moving. It’s a powerful reminder of the community of visionaries who built the foundation for what we recognize as the Black Arts Movement.

FW: How is your grandmother's legacy inspiring the Crocker’s 2028 show, Black Artists in California?

UL: Since the mid-1960s, my grandmother has stood as a central figure in the Black Arts Movement in California. It was during this time that she began publishing books and established her own print shop. In Los Angeles, she went on to found the Museum of African American Art, along with three other prominent galleries that became vital spaces for Black artists to create, exhibit, and be seen.

She also taught at Scripps College in Claremont, California, for fifteen years, profoundly shaping generations of artists and scholars. In 2007, Scripps honored her legacy by establishing the Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection, housed within the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery. These achievements represent only a small portion of her vast and lasting contributions.

Her influence reaches far beyond the Black Arts Movement, extending into the broader landscape of California art, where her leadership, scholarship, and advocacy left an indelible mark. I believe it is essential that her impact be fully acknowledged. Though some have attempted to overlook or minimize her role, her legacy is ultimately inescapable. It is woven into the very fabric of American art history.

Samella Lewis was not only a foundational architect in the emergence of the Black Arts Movement, but also one of its most powerful voices—broadcasting its vision and evolution to the world. I feel deeply guided by her spirit, not only in my curatorial work but in the creation of my own art. I am profoundly grateful for the blueprint my grandmother left behind and the legacy she entrusted to us. It is a true honor to carry her torch forward and to use the tools she gave me as inspiration in shaping our upcoming exhibition.