Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial to September 11

October 6, 2025

Read about exhibition "Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial to September 11," exploring works by Black artists made during the transitional moment from the late 1970s to the dawn of the 21st century.

OCTOBER 5, 2025 – JANUARY 11, 2026

Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial to September 11 is an exhibition exploring work by African American artists made during the transitional moment from the late 1970s to the dawn of the 21st century. The exhibition picks up where the Dixon’s 2023 exhibition Black Artists in America: From Civil Rights to the Bicentennial—the second in a three-part series, and on view at the Crocker in early 2024—left off. This third chapter of the exhibition continues to consider the ways in which Black American artists challenged the cultural, environmental, political, racial, and social issues of the last decades of the 20th century.

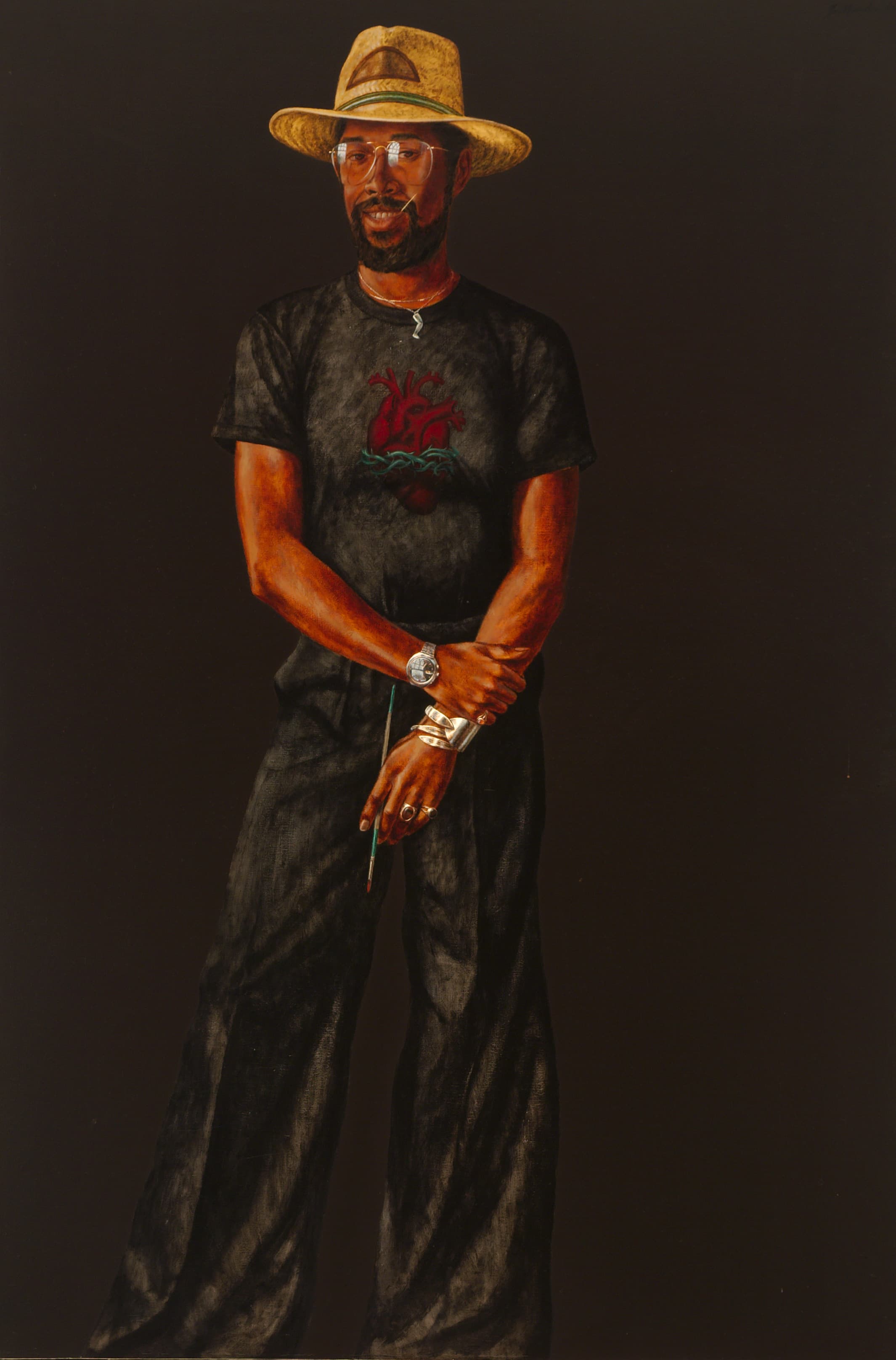

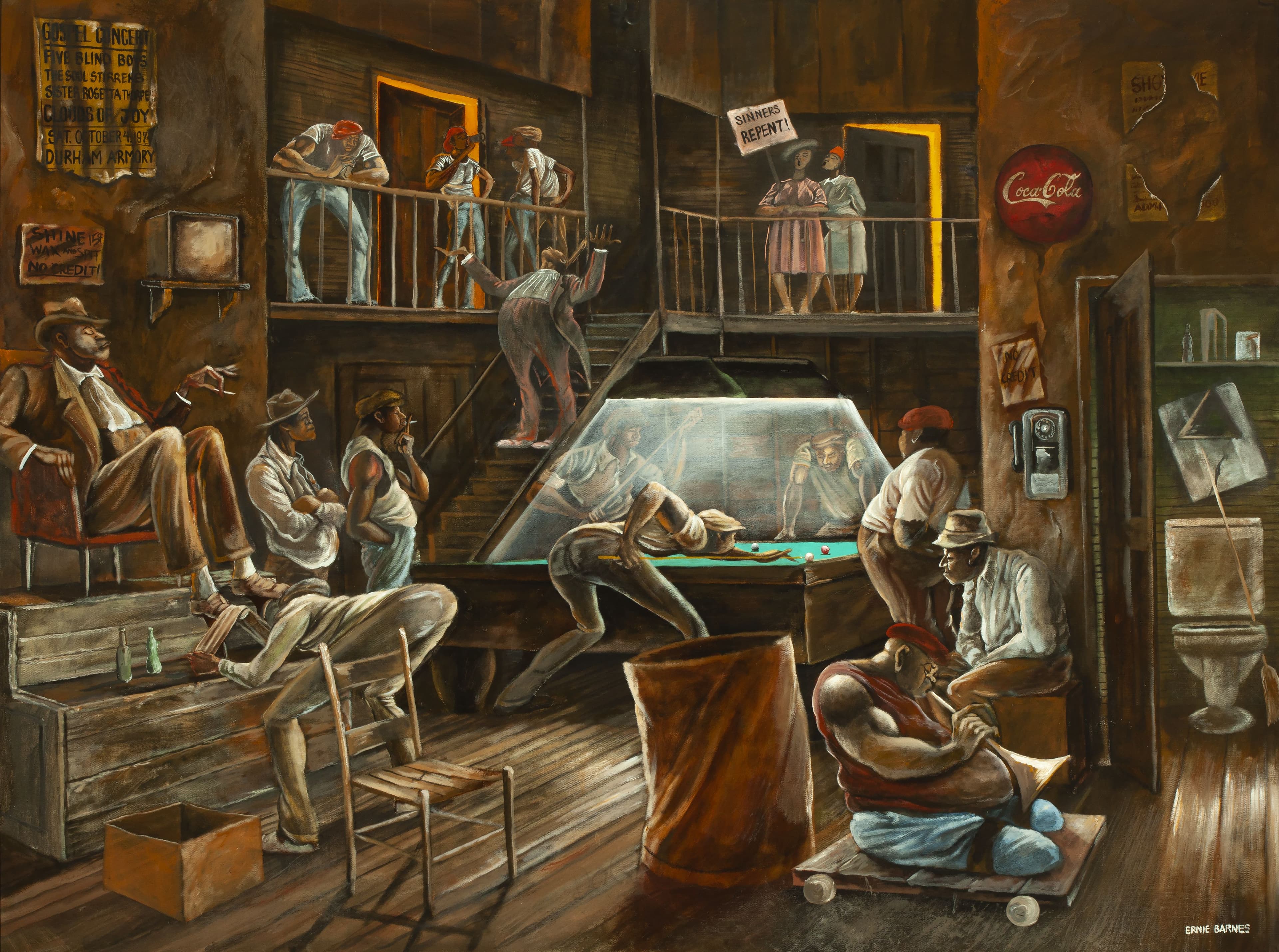

As white America grew increasingly patriotic in the runup to July 4, 1976, the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, many African Americans were either indifferent to or openly critical of that commemorative spirit. Deeply rooted prejudices persisted in nearly every sector of American society, including the visual arts. Black artists of all ages, from the highly successful to the virtually unknown, found themselves stymied by the closed society that was the mainstream art world. To be sure, an older generation of African American artists, including Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett [fig. 2], Loïs Mailou Jones, and Jacob Lawrence, had struggled through the harrowing Jim Crow era, and saw a viable and effective civil rights movement emerge in the 1950s and 1960s. They lived to witness advances in racial justice that would have been scarcely imaginable during their youth—yet there was still much work to be done. In the mid-1970s, Ernie Barnes [fig. 4], Barkley Hendricks [fig. 3], and Varnette Honeywood built on the successes of their predecessors and brought both affirmative and thought-provoking images of Black identity and culture into the mainstream. Sabbath (1977) [fig. 1], a collage by Honeywood, portrays three Black couples, the men in dark suits and the women in stylish hats, waiting in line to enter church on a Sunday morning. All six are seen in profile and each holds an emblematic object in their right hand—a church bulletin, a printed hand fan, and the Bible among them. The collage was widely admired and later featured among the works of art hanging in the home of the Huxtable family on The Cosby Show.

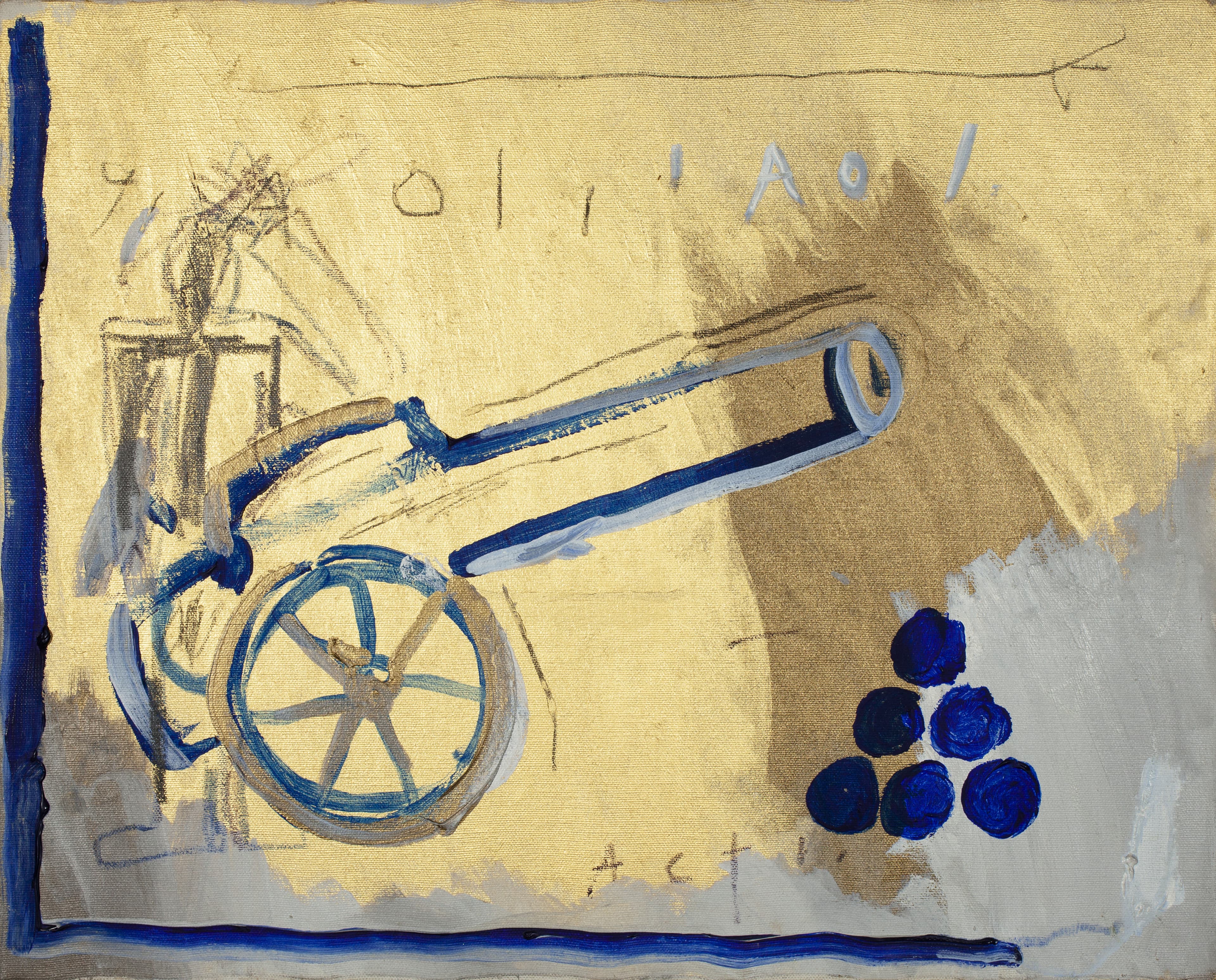

Not all African American artists of the 1970s and 1980s, however, were as deeply invested in realism or in naturalistic depictions of personal and cultural identity. Abstraction was also firmly entrenched in 20th-century art, and many Black artists continued to explore the possibilities of nonobjectivity. A variety of abstract styles coexisted in the works of Black artists, including the hard-edge painting of Jennifer Ray and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s gestural, graffiti-inspired paintings. Basquiat’s brief but brilliant career witnessed a meteoric rise to the top of the American art scene in the boom years of the 1980s. Often described as “searing” and “rebellious,” his work combines influences of Pop Art, Dada, and the graffiti he encountered and produced growing up in Brooklyn. Painted just as his star was beginning to rise, CANNON (ACT 1) (1981) [fig. 5] teems with the artist’s singularly raw energy. Coarsely rendered but clearly legible, the cannon that dominates the composition alludes to history as well as conflict and violence. The title suggests the beginning of a historical epic and, indeed, the artist was entering a new phase of his career, merging spontaneous street art with a more traditional approach to painting on canvas.

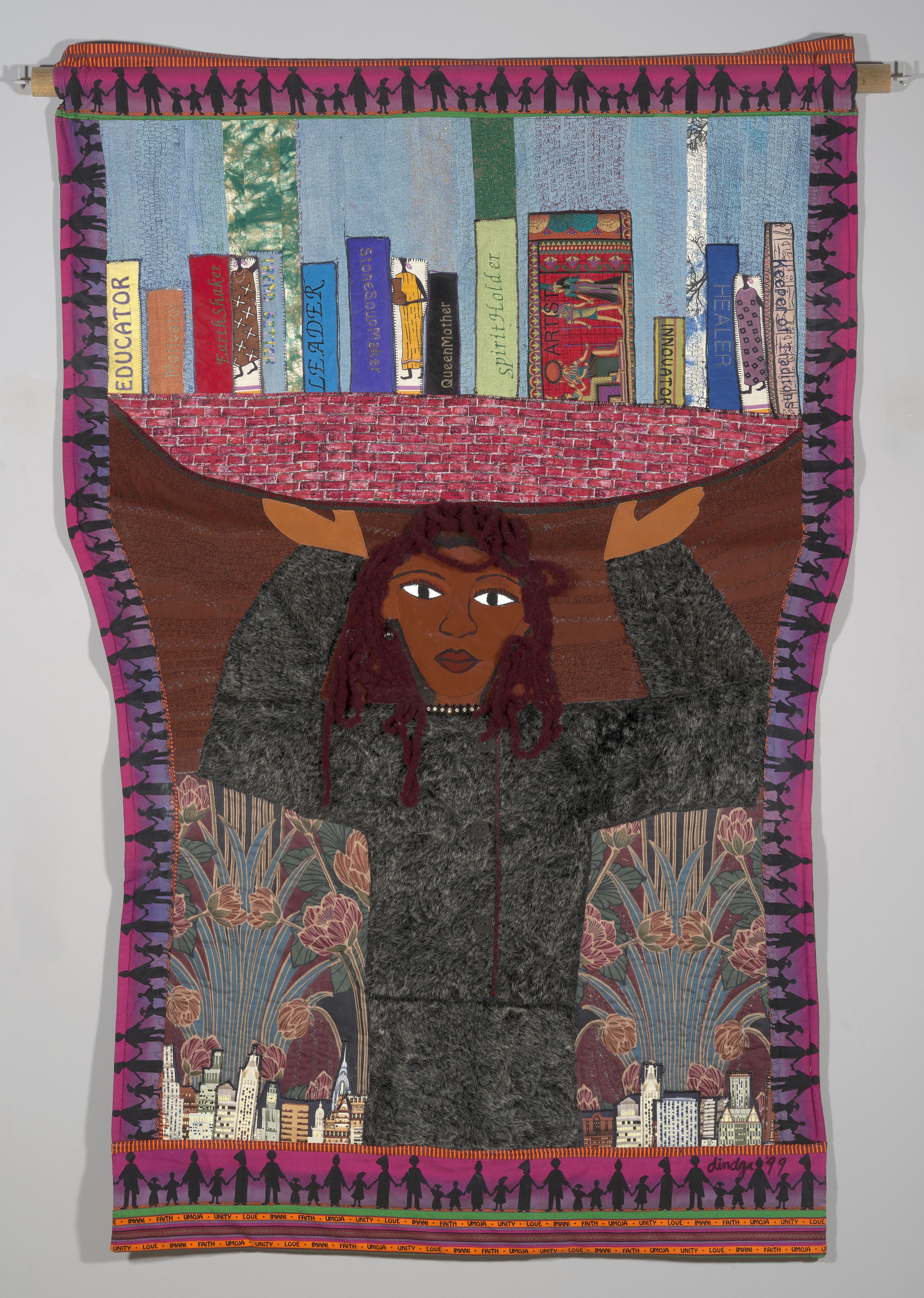

Artists of the 1990s were in the unique position of looking back at nearly a century of immense historical change while anticipating not only a new century, but a new millennium. Perhaps paradoxically, some artists often attempted to look ahead by mining the past for imagery. Personal and collective memory come together in the works of artists such as Samella Lewis, Dindga McCannon [fig. 7], and Whitfield Lovell, who made poetic, melancholy works that yearn for a connection to Black ancestors. Samella Lewis was an accomplished printmaker, teacher, gallerist, and writer who made profound contributions to the history of art. In her lithograph Cleo (1996) [fig. 6], a young girl holds a bouquet of yellow roses. Her face and neck speak to the influence of West African sculpture on European and American 20th-century art. The girl is somber, her gaze directed upward, and her face, ringed in yellow, seems to levitate away from her ears and hair. Cleo, or Clio, is also the name of the Greek muse of history, the daughter of memory. Bearing flowers as an offering and positioned so that the hint of a cross can be seen behind her, the girl reminds the younger generation not to forget the past. A yearning for connection to ancestors is palpable in the art of Whitfield Lovell, who uses old photographs as core imagery. The pictures he mines are usually not those of family members but anonymous African Americans who might otherwise have been lost to history. In Epoch (2001) [fig. 8], Lovell translates and enlarges an image of a World War I soldier into a charcoal drawing on wide, vertical wooden planks, the warm brown color and visible grain of which create a patina similar to old sepia-toned photographs. The soldier’s presence suggests a history of contradictions that military service posed for African Americans—a subject that again entered public discourse following September 11, 2001. At once a means of finding employment, learning new skills, and traveling beyond the confines of the segregated United States, military service historically meant that Black servicemen were representing US institutions that frequently denied them and their communities the basic civil rights for which they were fighting. Lovell’s found objects function like a shrine, enlivening and enriching the drawings to further imagine and extend the lives of long-deceased individuals.

Buoyed by the civil rights activism of the 1950s and 1960s and the significant legislation that followed, Black artists working between the 1970s and early 2000s saw glimmers of hope for real and lasting change. Encouraged by the modest progress of the last quarter of the 20th century, they maintained pressure on institutions, granting agencies, and the market as never before, pressure that gradually—and finally—began to bring change to the art world.

Black Artists in America: From the Bicentennial to September 11 is curated by Dr. Earnestine Lovelle Jenkins, professor of art history at the University of Memphis, and includes more than fifty paintings, sculptures, and works on paper drawn from public and private collections across the country. An accompanying catalogue featuring essays by Dr. Jenkins, Dr. Julie McGee, Dr. Ellen Daugherty, and Kevin Sharp will be published by Dixon Gallery and Gardens, in association with Yale University Press.