Arts, Letters, and Power Van Dyck and the Portrait Print

September 22, 2025

Examine how Van Dyck’s Iconography series used portrait prints to elevate artists’ status alongside nobles and intellectuals.

From our modern vantage point, it can be difficult to recognize what made Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck’s (1599–1641) series of portrait prints, now known as the Iconography, so radical. In capturing the likenesses of the nobility, military leaders, thinkers, and artists of the time, Van Dyck displayed a familiarity with the era’s power players not unlike artists today, many of whom also rub shoulders with celebrities and politicians or are splashed across our social media news feeds. In the 17th century, however, the status of the artist was still an unresolved question. Artists had long been associated with artisans and craftspeople in the European social order as producers of consumable goods, no matter how fine and costly those goods were. Increasingly, however, artists sought entry into the realm of the intellectual, likening themselves to poets, scholars, and philosophers. The portrait— specifically, the artist’s self-portrait—was an essential component in early modern debates regarding the artist’s status.

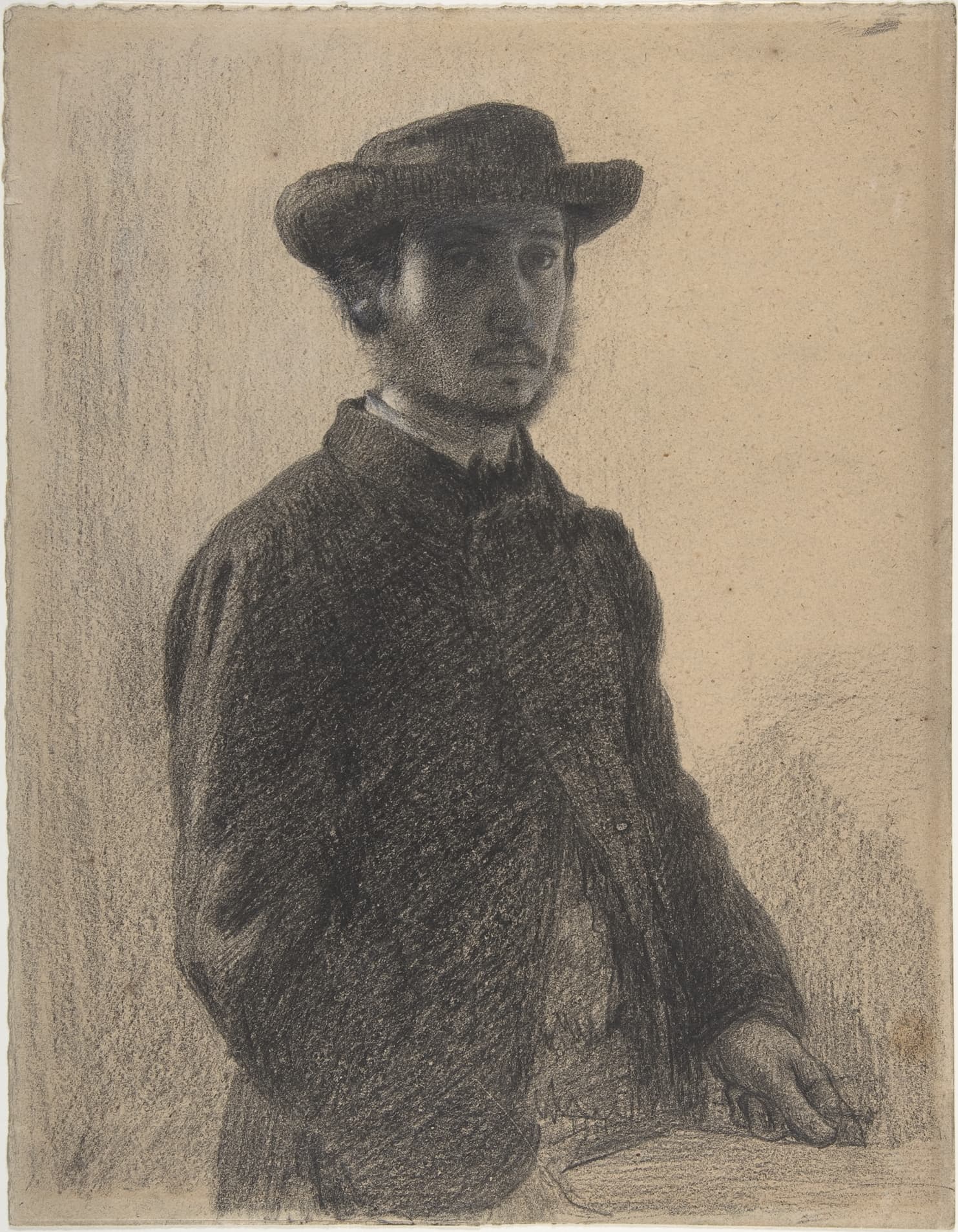

Although Anthony van Dyck was far from the first European artist to portray himself in a self-portrait, he expanded upon the tradition by depicting himself [fig. 1] and many of his peers in the highly reproducible medium of print. In assembling a series of portraits of artists alongside those of the dignitaries and scholars of the day, Van Dyck made a clear argument for the intellectual and cultural importance of his profession—an argument that would influence generations of artists, from Rembrandt to Edgar Degas [figs. 2–3].(1)

The exhibition Arts, Letters, and Power features a selection of etched and engraved portraits from a recent gift by Margaret and Timothy Brown of 188 works from Van Dyck’s Iconography series. The prints emphasize the variety of individuals in the series, the complex relationships between the many artists depicted, and Van Dyck’s incredible skill at portraying not just the likenesses of his sitters, but their distinctive qualities and attributes. The Iconography, which Van Dyck began in the early 1630s, was modeled after the artist’s drawings and paintings. While Van Dyck etched at least 15 of the portraits himself, the rest were produced by prominent printmakers in his circle, both during and after the artist’s lifetime. Many of the images were issued in multiple states, a reprinting with additional changes.(2)

Like many of his peers, Van Dyck came from an artistic family. Born in Antwerp in 1599, he was the seventh of 12 children to Frans van Dyck and Maria Cuypers. Frans van Dyck was primarily a prominent silk merchant, but had some artistic training as a painter, while Maria, who died when Van Dyck was only eight years old, was an accomplished embroiderer and possibly his first instructor in the arts. Van Dyck’s talent as a painter was evident early in his training. The young artist eventually entered the studio of Peter Paul Rubens [fig. 4] and became his chief assistant. The mentorship he received under Rubens was instrumental in developing Van Dyck’s style and reputation as a skilled portraitist. Scholars have argued that the impetus for the Iconography series was, in part, an attempt to match Rubens’s abundant output of prints, and that Van Dyck understood, through Rubens’s example, the value of printmaking as a vehicle for fame.(3)

Like Rubens, Van Dyck spent significant time in Italy and France, painting many prominent members of the nobility, where he also encountered the work of Veronese, Titian, and other illustrious Italian artists of the late 16th century. These early influences shaped Van Dyck into a masterful colorist, a skill he used to emphasize the elaborate costumes of his elite clientele. At the same time, he learned a keen sense of composition and positioning that flattered his sitters and imbued his portraits with a sense of lifelike grace. For instance, the engraving of Béatrice de Cusance, Duchess of Lorraine [fig. 5], reframes the original full-length painted portrait as a half-length print, which draws the viewer’s eye downward to Béatrice’s elegantly positioned hands, one clutching her overskirt, the other pushing back a billowing drape. Van Dyck consistently injected his figures with lively individualism through detailed attention to naturalism and dynamic positioning, such as in the portrait of Inigo Jones—the English architect responsible for the layout of Covent Garden, among other notable projects—where the drafting paper in Jones’s hand dangles beyond the frame, casting a shadow across the identifying inscription and bringing Jones into the viewer’s space [fig. 6].

Individual fame and legacy were of great concern for Van Dyck, as a matter not only of personal pride but of economic security. Court appointments guaranteed a stream of income and provided access to noble clientele as future patrons. The original design for Van Dyck’s self-portrait is just a fragment, depicting only his head and a suggestion of the outline of his collar. The finished engraving by Lucas Vorsterman the Elder [fig. 1], however, prominently displays Van Dyck’s chain of office, granted to him upon his knighthood in 1632 by Charles I of England, whom he served as court painter.

The inclusion of notable collectors such as Nicolaas Rockox (1560–1640), who sits among a variety of books and sculptures, appears to celebrate the role of the collector in increasing an artist’s fame [fig. 7]. Prints in series encouraged collectors not only to delight in assembling a complete set, but also to curate their collection. Early modern print collectors frequently bound their acquisitions in volumes, of which there are two in this exhibition. The collector, not just the artist, was made the arbiter of how the series could best be presented—perhaps chronologically, by nationality, or by other preferred criteria.(4) Anthony van Dyck never indicated how many subjects he intended to include in the series, or in what order they should be presented. This exhibition, not unlike the collections of Van Dyck’s era, participates in the centuries-old act of assembling portrait prints from the Iconography, furthering the fame of the many hands involved in the prints’ creation.

(1) Victoria Sancho Lobis, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and the Portrait Print (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 49–55.

(2) Marie Mauquoy-Hendrickx, L’Iconographie d’Antoine Van Dyck: Catalogue Raisonné, 2nd Edition (Brussels: Bibliothèque Royale Albert I, 1991).

(3) Lobis, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and the Portrait Print, 36.

(4) Lobis, 25.